A late offering, for which I apologise, and a hastily written one. There have been many calls upon my time, too many of which involve peering at a screen.

Reasons to be cheerful

1. January, drear, dark, dry, sempiternally long January is at an end. When I say ‘dry’ I mean in the sense of abstinence from alcohol. Certainly, and emphatically, not dry meteorologically.

2. There are signs of spring. Towards the end of January there is a shift in the light which tells us we are past the deepest darkness. At last the mornings are growing lighter apace with the afternoons. Although my snowdrops are not in flower, their dark green pointed leaves have broken the surface of the saturated ground, and the usually later primroses are already blooming on south-facing banks, and even beside the paths through the woods.

3.The birds are singing; not the full territorial spring symphony of mating and nesting, but the over-wintering residents are tuning up in the mornings. There is a particularly noisy song thrush in the trees opposite, two insistently repetitive great tits, my garden robin and wren, the melodious blackbird, and many others. Flocks of fieldfares settle on the fields and fly up again in one swooping movement, and a lark rose high over me as we walked on the flat and windswept airfield. Rooks circle and caw, and the crows’ “parp parp” sounds like ancient klaxons.

4.Making marmalade, the annual new year treat that fills the house first with the sharp tang of cooking citrus, and then with the sweet comforting warm smell of caramelised oranges. I thought this year that the Seville oranges might be scarce because of Brexit difficulties with imports, but they appeared on time, the lumpy rather shabby-looking oranges, which remind me of walking through small towns and villages in Andalucia and Extremadura in the autumn, the ground littered with them, split and squashed beneath my boots.

4.There are moments of transcendence. As we came home across the Common one frosty morning the rising sun caught the wing tips of the hunting barn owl, and – fleetingly – transformed them into a translucent roseate gold. Such instants of grace illuminate a whole day, and number among the blessings which must be counted if we are to survive these strangest of times.

Among these reasons for optimism, the fact that we have had some “real” winter weather appears to sit oddly, for who would want frost and snow? Last year there was scarcely any frost, and climate change promises more warm wet winters. But frost and snow should be the norm, and there is a comfort in the right order of things in a changing world. We had quite a blizzard, turning the landscape monochrome, and piling up the snow on the window sills. As they say round here, “that snoo.”

Hard frosts are a joy, freezing the ankle-deep mud into sharp ruts and ridges, almost more painful to walk on than rock, but allowing passage along impassable footpaths and over fields usually too claggy to contemplate. We return on these mornings, boots and paws clean and dry. The dog rolls ecstatically on icy grass. These are the champagne days, bubbling and fizzing with the energy that comes from the all-too rare sunshine and blue sky. As with everything good, it seems, they do not last.

All-too rare. For, surpassing even last year’s record totals, the rainfall has been constant and heavy, and the sky louring and dark all day, the clouds pregnant with water in unprecedented quantities. People are saying “I’ve never seen it like this, not in all the years I’ve been here.” Walks involve long detours to avoid floods, the roads are awash, and I have lost count of how often I have had to pump out my drive so the postman can come up dry shod. Farmers cannot get on the land – except for one neighbour who gets his tractor out before daybreak on days when the frost is hard, and ploughs then.

It would be peculiar, and in a way disrespectful, not to mention the wider context of this January. The new year had scarcely begun when we were locked down for the third time in ten months. A combination of social mingling and travelling at Christmas, and a new variant of Covid 19 – of swift and fierce contagion – had hospitals all but overwhelmed, and deaths reaching record levels. One day more than 1800 bereavements were recorded. Maybe we are becoming war-weary and inured to these losses, the daily statistics, unless they affect us personally. But whoever thought to see so many deaths in one day in peace time? One Covid denier (“It’s just ‘flu”) has now seen three friends die, and at last urges prudence. And yet still, despite lockdown, rules, strictures, fines, horrific scenes nightly on our televisions, still the disease spreads.

Covid is cruel. Its selection of those victims most viciously attacked seems arbitrary. But the irony and the tragedy is that the very ways human beings connect – through speech and touch – are the vectors of disease and death. We can unwittingly kill those we love the most, or they us, and the burden of guilt and loss will last for decades.

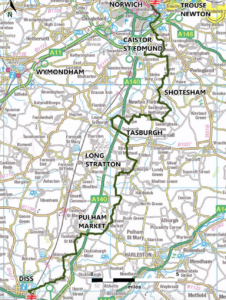

Some readers remark on the melancholy tone of these chronicles. These are tragic, difficult times. But I’ll move on to my favourite theme – Suffolk. I live about 20 miles from Sutton Hoo, the subject of the film “The Dig”, released last week. It is a film very much of two halves, and the first – before the excavation is swamped with archaeologists and cluttered with box office undercurrents of love and sex – is beautiful. It is as muted and undramatic as east Suffolk itself, gently hinting at a metaphor of both things and feelings hidden and under the surface.

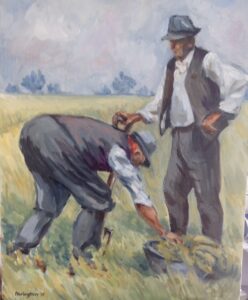

Ralph Fiennes transforms himself into an old Suffolk “boy” to play Basil Brown, the self-taught archaeologist, astronomer, and polymath. Fiennes has the Suffolk accent – those slow diphthongs – absolutely right (regional English accents portrayed on the screen are so often cringe-making). When I first came to Suffolk in the early Seventies there were many in the village who dressed exactly as Fiennes/Brown in the film, who cycled long distances if they needed to go somewhere, who spoke the same, stood the same, moved the same. This is the Suffolk of Harry Becker, of “Akenfield”; and I have watched the first half of the film through three times now, gazing at the facsimile of a lost age, and a lost world, the nostalgia all the sharper because of the uncertain times we are living in.

Most of my life is indeed lived through a screen now, for lockdown perdures, and there are at least another five weeks of isolation to come. Friends, family and colleagues live in my computer; entertainment comes on a different screen. I little thought, three and a half years ago, when I started this monthly record that I should be recording a global pandemic, and that my world would have shrunk to the confines of garden, Common and the fields and woods around them.