“New month, new weather,” they say, and so it turned out to be. After the interminable dark, cold and wet suddenly spring appeared. Maybe a little hesitantly, but there has been sun, blue sky, even warmth.

And with it my spirits rise, as steep and sudden an ascent as the spike in the price of oil. But if I dwell on matters geopolitical I shall talk myself out of the joy that comes with increasing light, and days without rain. Now the sound of tractors is heard once again, for the land is just firm enough now to get on with top-dressing and mucking. Standing water on the roads has dried sufficiently to reveal the extent and depth of the potholes, those witnesses to our fracturing infrastructure, and costly causes of damage to our vehicles. Suffolk was recently rated one of the worst in England for road maintenance and potholes receiving a “red” rating in a January 2026 Department for Transport (DfT) report. Often in our little lanes, with their heavy traffic of tractors and animal transporters, there seems more hole than road.

And with it my spirits rise, as steep and sudden an ascent as the spike in the price of oil. But if I dwell on matters geopolitical I shall talk myself out of the joy that comes with increasing light, and days without rain. Now the sound of tractors is heard once again, for the land is just firm enough now to get on with top-dressing and mucking. Standing water on the roads has dried sufficiently to reveal the extent and depth of the potholes, those witnesses to our fracturing infrastructure, and costly causes of damage to our vehicles. Suffolk was recently rated one of the worst in England for road maintenance and potholes receiving a “red” rating in a January 2026 Department for Transport (DfT) report. Often in our little lanes, with their heavy traffic of tractors and animal transporters, there seems more hole than road.

Early spring has a beauty which snatches at my heartstrings more insistently than the later lushness of April or May. It took only a few days for the first leafbuds to appear in the hedges, for the blackthorn to blossom, and for the sweeping grace of the weeping willow to green. All other trees are still skeletal, stark against the sky – the oaks gnarly and solid, the ash buds deep sooty black:

More black than ash-buds in the front of March, wrote Tennyson.

Now there are constellations of primroses on the banks of ditches, alongside the paths we walk. In a wood I come across an expanse of violets. If you get down on your knees and put your nose close the scent is delicate but unmistakeable, redolent of the scent bottles on grown-up dressing tables when I was young.

“O, it came o’er my ear like the sweet sound / That breathes upon a bank of violets, / Stealing and giving odour!” (Twelth Night)

Fortunately I walk early, and am unlikely to be surprised in this inelegant pose.

As we approach the Equinox daylight races in; every morning giving us one, two even three more minutes’ earlier sunrise: no longer any need for a torch as the dog and I go out at six, nor for her glow-in-the-dark collar.

The eastern sky shows a misty golden glow heralding a day filled with light, yet in the west a full moon hangs low just above the trees. The volume of the birdsong increases, the larks invisible high above singing insistently, while across the fields I cannot count the number of brown hares I see running. The dog sees them too and stands alert, quivering, longing… but she is obedient and turns back when I whistle.

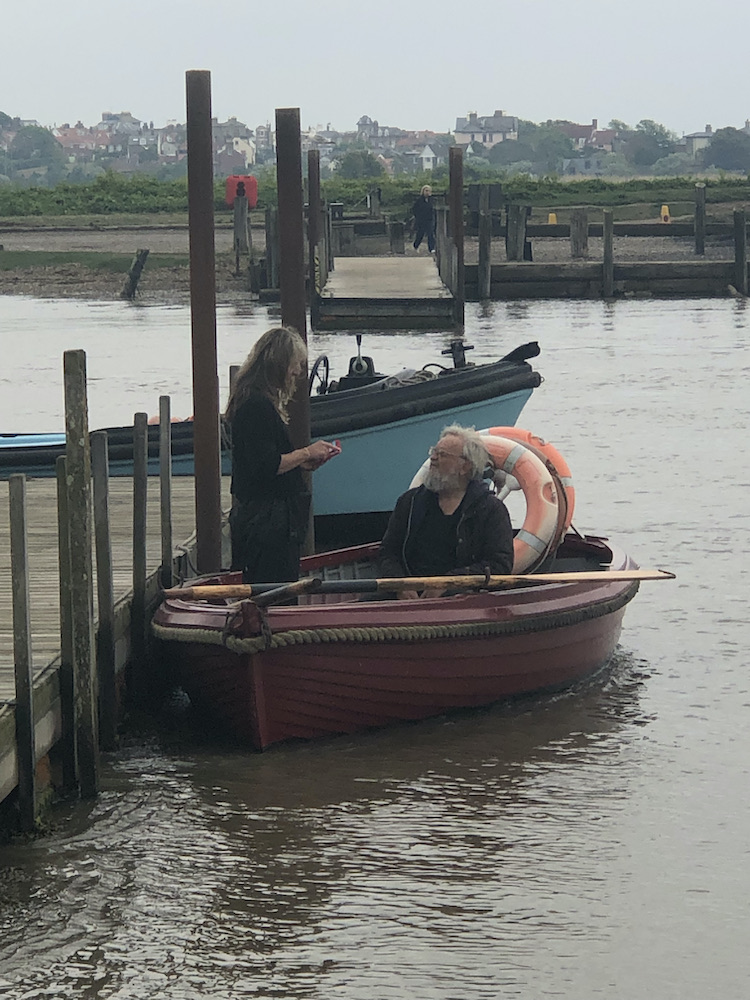

It is a time of year that suits Suffolk. We live in a kind landscape here close to the Waveney Valley. It is a peaceful river, rising in a fenny patch west of Diss, and flowing gently for nearly 60 miles, separating us from Norfolk, until it meets the River Yare in Breydon Water and so goes on to the sea. The Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names 2003 tells us the earliest attestation of the name is from 1275, Wahenhe, from *wagen + ea, meaning the river by a quagmire. Yes, that sounds about right this year…

Along its course were many mills – Scole, Syleham, Needham, Mendham, Ellingham, and others lost to time. Alfred Munnings was born at Mendham Mill in 1878, and in his earlier days before he became a society painter recorded the life and working of a busy mill at the turn of the century, centering on horses and horse-drawn carts.

Not long after Munnings left Suffolk, another painter arrived, not far away, in Wenhaston. This was Harry Becker whose paintings and drawings, many done swiftly with a few lines or brushstrokes en plein air, record the now lost activities of pre-mechanised agriculture.

Mendham shows us the loveliest of the Waveney. Tranquil marshes and meadows that could have come from an Old Master Dutch landscapist.

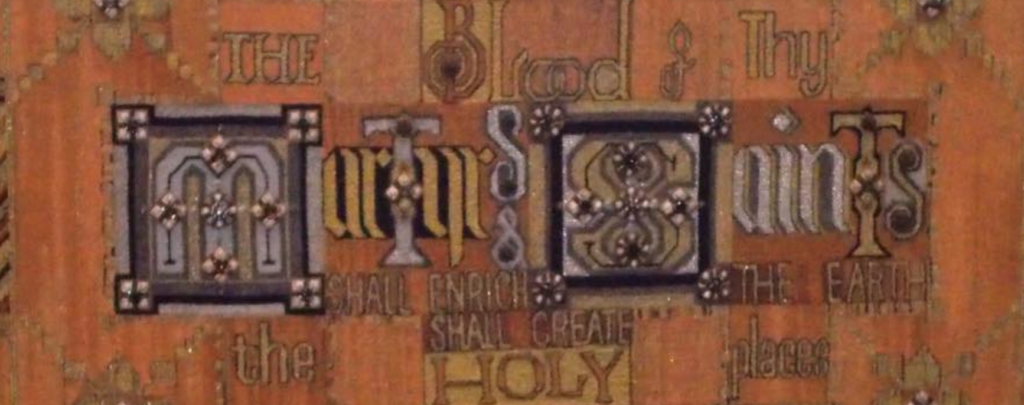

After you cross the river into Suffolk the land rises steeply (steeply for Suffolk, that is) taking you up into a maze of tiny villages – the Saints country – where you could almost think yourself back in the days of Becker and Munnings. When we first ventured into the Saints, half a century ago, we drove round and round, the old finger posts deceptively promising a way out, but leading us back circuitously whence we had come. And not surprisingly were we ‘foreigners’ confused by these names: the South Elmhams (pronounced ‘Ellum’) – St Cross, St James, St Nicholas, St Peter, St Margaret, All Saints, St Michael and St Nicholas; all these cheek by jowl with the Ilketshalls – St Margaret, St Laurence, St Andrew, St John.

Driving home through the Saints one fine soft morning recently, I stopped to watch a buzzard seen off by two rooks, like two Spitfires harrying and hounding a Heinkel.

More reason to be grateful for fine weather…a dry Wednesday and Sunday mean pétanque is not cancelled. Since last summer pétanque has become a passion. Thirty years ago in the south of France where I lived I learned to play, somewhat less than competently. There each village had its boulodrome, or at least a terrain on the place, and provided scenes and sounds of the Midi which now seem clichéd. It was a game to be taken seriously.

More reason to be grateful for fine weather…a dry Wednesday and Sunday mean pétanque is not cancelled. Since last summer pétanque has become a passion. Thirty years ago in the south of France where I lived I learned to play, somewhat less than competently. There each village had its boulodrome, or at least a terrain on the place, and provided scenes and sounds of the Midi which now seem clichéd. It was a game to be taken seriously.

And no less so now in Suffolk – in a neighbouring small town with its two terrains on the community playing field. I saw an advertisement on local social media calling for new members, so decided to give it a go. The blush of youth has long since left these players, and the talk when they meet is of arthritic joints and the afflictions of age, but they play in deadly earnest. I was made very welcome, but no quarter was given to the newbie. Points are fought fiercely with measuring tape and – if need be – calipers.

I love that. Fun has been in short supply in the past couple of years, but pétanque restores me, takes a hundred percent of my concentration, and – for a happy hour or so – banishes all cares.

It provides, too, a welcome break and relaxation from work; for, dear reader, even as I approach my eightieth year I need must work to keep the proverbial wolf from the door, to keep the dog in the style to which she is accustomed, and – in our current geopolitical chaos – to buy heating oil and petrol

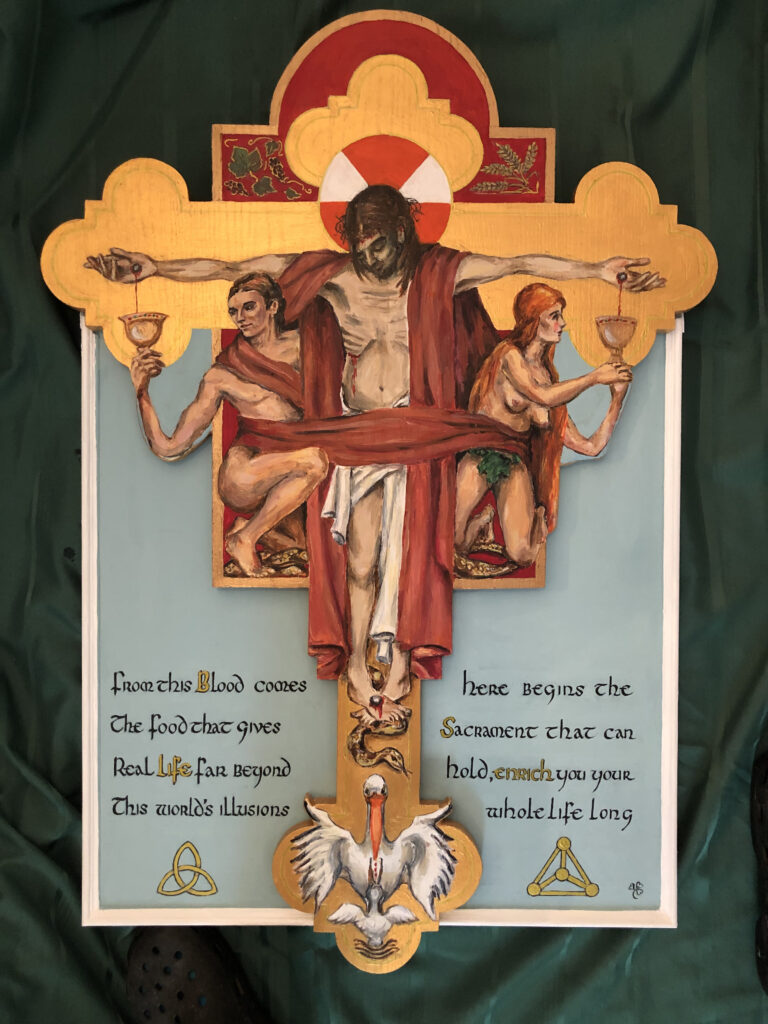

Rarely these days does a portrait or other art commission come my way (though I am working on one currently), so I do what I have done on and off for some 45 years: editing and proofreading. It has its moments, but mainly I wade through the tedium of hyperprolix wannabe authors (I fear there is little chance of discovering the next Booker sensation) and the complexities of legal and commercial matter (which pays better).

Another month. March came in like a lamb. Will it roar out like a lion?