Time passes. The days merge. My hair grows.

And there I could end my record of the month of May 2020. A torpor has descended; tasks are postponed – a Covid procrastination, for why do them today when tomorrow will be the same, and the day after? I feel fixed and unmoving in a no man’s land where time – though it passes both pleasantly and all too rapidly – also seems immobile.

My world has shrunk. Lockdown has confined me to those very places of which I set out to write: my garden, the Common, and the fields and woods beyond. Outings are rare in the extreme – a slow puncture to be mended; chicken feed to be collected. I watch, distantly, the easing of restrictions, and neither want nor need to join in the emerging of the herd.

It would be wrong but easy to think that life was passing by unlived, that this year – one of the perforce few remaining – was being wasted, devoid as it is of the usual rush and bustle. The lived moment is life, and the value we put upon it – good or bad, pleasurable or painful, solitary or social – is just that, our subjective take.

Nonetheless, we are human and we experience pleasure and pain, however small our world has become. For me, blessed as I am, May has brought great pleasure…and a little pain. It has been the sunniest May since meteorological records began in 1929, and the driest in 124 years. Day after day the sky has been a Mediterranean blue and the sun has beaten down upon an increasingly parched earth with a dazzling intensity. From time to time there have been violent and rough winds to shake the darling buds, and these have served to dry the land still more. I have never seen grass burned brown in May before.

The old country proverb once again holds good:

Oak before ash, we shall have a splash.

Ash before oak, we’re in for a soak.

Even a splash would be good….

In fact this year the darling buds of May had all opened and burgeoned well before the month began, for at an estimate most vegetation seems four or five weeks ahead of where it would have been a few decades back. The chestnut candles are long since dimmed; the hawthorn had dropped its blossom by mid-month – the indecent smell of it gone now.

The barley has “eared up,” as we say round here, and the million filaments shimmer in the morning light. The wheat begins to grow tall, blue-green. The uncut roadside verges frothed briefly with bridal cow parsley, and the starry white flowers of the pungent wild garlic have faded. The elderflower is out; dogroses cascade in the hedgerows; ox-eye daisies dance in the breeze. Summer races ahead, outstripping spring.

This early flowering and seeding brings with it another sort of lockdown for me: the grasses are seeding and hay fever limits the time I can spend out of doors. On our morning walks I set out, duly medicated and sprayed and eye-dropped, in dark glasses, and my eyes and nose smeared with Vaseline. The dog precedes me through the long grass me sending up golden clouds of pollen dancing in the low sun.

Summer has come early; the electric lime green of spring matured too quickly. Soon the glory of morning birdsong will fade, little by little, unnoticed, till suddenly one morning we hear… silence. The lark may still sing high on the wing, and a yellowhammer may still announce “Little-bit-of-bread-and-no-cheeeeese,” but that exuberance and joy (how we love to anthropomorphise the aggressive avian macho mating defence of territory!) will be gone till next spring. And thoughts come unbidden – shall I live to hear it? Live in the moment. Live in the moment.

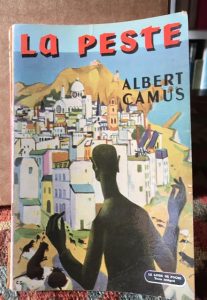

The continuing pandemic, and the feckless floundering of our government, have sent me to my bookshelves for my ancient copy of Camus’ “La Peste” (The Plague), gathering dust since university more than half a century ago. The plague in the novel is generally taken to be a metaphor for the rise of Fascism, though some read it as a diatribe against capitalism and materialism. Given the current situation, especially in the United Kingdom, it can equally well be read as a literal account.

The infection comes to a town that is obsessed with business, a place where the sole object seems to be the pursuit of wealth. The authorities are slow off the mark, reluctant to act because of the economic consequences and the reputational damage to the town. Mitigation measures are mired in bureaucracy, until, as fevers spike and bedsheets are soaked from night-sweats, there is no choice but to quarantine the town: “We should not act as though half the town were not threatened with death, because then it would be….We must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody’s face and fasten the infection on him. What’s natural is the [virus]. All the rest—health, integrity, purity—is a product of the human will, of a vigilance that must never falter.”

Businesses complain about being closed down. Social distancing is not properly observed. There are hoarders and profiteers. Before long, hospitals are overwhelmed; medical supplies are scarce; a makeshift quarantine camp is established; and the police do their best but are sometimes heavy-handed. The cast of characters is eerily familiar: the Prefect who begins in denial (“There are no rats in the building,” as the rats die all around them), but then has no choice but to bow to the expertise of his medical advisers once the exponential spread of disease becomes apparent; the chap who tries to escape the lockdown, heedless of the risk of spreading infection beyond the walls. It could have been written in the past two or three months as we witnessed the Cummings and Goings of our masters.

Aristotle argued that, thanks to the gift of language, man is destined to be a social and therefore a political animal. Today I, and many, live in the paradox of an enforced solitude whose window on society is perforce through a screen, mediated by a cacophony of voices – politicians, pundits, scientists. We see the world through a television screen; we see our friends and families through a computer screen. Through a glass darkly to a world where we can look, but we cannot touch.

Can I end this month’s chronicle on a note of optimism? I can say that the number of cases in this country has fallen, that death rates are down, that the first tentative steps of a return to previous existence are being taken by some. I can say that some of the seeds I sowed in early spring are already providing food, that the rest will soon follow; that baby birds are fledging; that there is a foal on the Common.

Love it, Mary. Even better than usual. Have you thought of publishing your monthly musings? You have captured everything I feel but lack the ability to express. Thank you.

Thank you, Heather. You could be my agent??

C ‘ est très beau ce que tu écrits je reconnais ta profondeur d ‘ âme. J ‘ aime les photos et peintures qui accompagnent les textes . Par le souvenir je te revois très bien dans ta jolie maison et ton jardin . Je t ‘ embrasse ton amie française

Merci, Nicole. Tu l’as fait traduire? Bisous