And late to the party came summer. Very late. A last-minute arrival. But she came, and dressed in gold.

For almost all the month golden day succeeded golden day of cloudless skies. It was warm, it was still, almost no breath of wind. The nights, though they came early, were summer nights. With the warmth my tensions and stresses disappeared; with the sun energy levels rose. Dark and gloom were forgotten.

Such stubble fields as remained were bleached white and striped with green where fallen grain had germinated. The plough as it slowly swallowed them sent up clouds of dust from the bone-dry earth.

Although my own energy flooded back, the windless anticyclonic weather contributed to an acute shortage of power in this country. Wind power failed, after one of our least windy summers since 1961.The UK’s wholesale energy markets reached record highs after a global surge in demand for gas following a cold winter that left gas storage facilities depleted, plus a rebound in post-lockdown energy demand across Asia. A race to refill gas stores before the return of colder temperatures caused market prices to surge. But then came a series of nuclear reactor outages and the shutdown of a major power cable that brings in electricity from France. Energy prices rose; suppliers went bust.

Then came a panic over petrol supply because there are not enough tanker drivers, occasioning more price rises Nor are there sufficient HGV drivers to stock shelves in shops. And nor are there workers for our farms. Nor are there the carbon dioxide supplies needed for abattoirs or freezing and chilling food. No turkeys for Christmas, no toys either, we are told. On the day I am writing this the Covid furlough scheme ends; there will be unemployment. In a week the £20 a week uplift to Universal Credit payments will be withdrawn.

A winter of Dickensian misery and poverty awaits many, the result of Brexit, Covid, and an almost unbelievable mix of incompetence and insouciance on the part of our government. So much was predictable, even if a pandemic was not (though in truth it could, and should, have been foreseen). I find it hard to moderate my anger, and equally hard to know how to help, other than contribute to the food bank and support aid agencies. Aid agencies! In the country that pioneered the Welfare State! What have we become?

One hot sunny day saw me driving to the West Midlands to deliver a painting commission (of which more in a moment). Summoning up my courage, I had no choice but to take the drive of death that is the M6, and I find it hard to believe that there is a shortfall of truck drivers. It would have been hard to fit in many more on some stretches, as they weaved in and out of motorway lanes at high speed. I returned the next day, back and shoulders tensed and sore from the stress, and shaky from fear. But return I did, and filled my car with petrol minutes before the first news broadcast enjoining drivers not to panic at potential shortages of petrol deliveries. Days of queues at petrol stations followed, with pumps running dry, and people not able to get to work.

To sum up: we’re in a mess, and worse is to come.

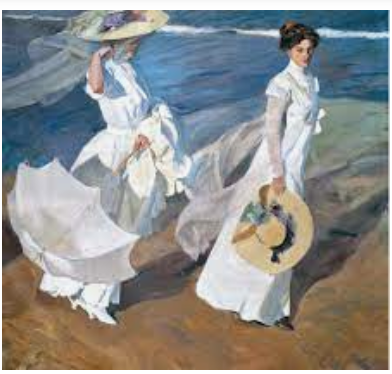

So why was I risking life and limb to drive to Wolverhampton and back? A former colleague of mine from long ago is an expert on John Singer Sargent. Sargent ( 1856 –1925) was perhaps the most successful portrait painter of his era, as well as a gifted landscape painter and watercolourist. His society portraits are notable for the way he depicts fabrics, and the use of light upon these, comparable with the work of Sorolla, his contemporary in Spain. Towards the end of the Great War he was commissioned by the British War Memorial Committee to document the war, and as a result of time spent on the Western Front in 1918 he produced the great (in both senses) “Gassed.”

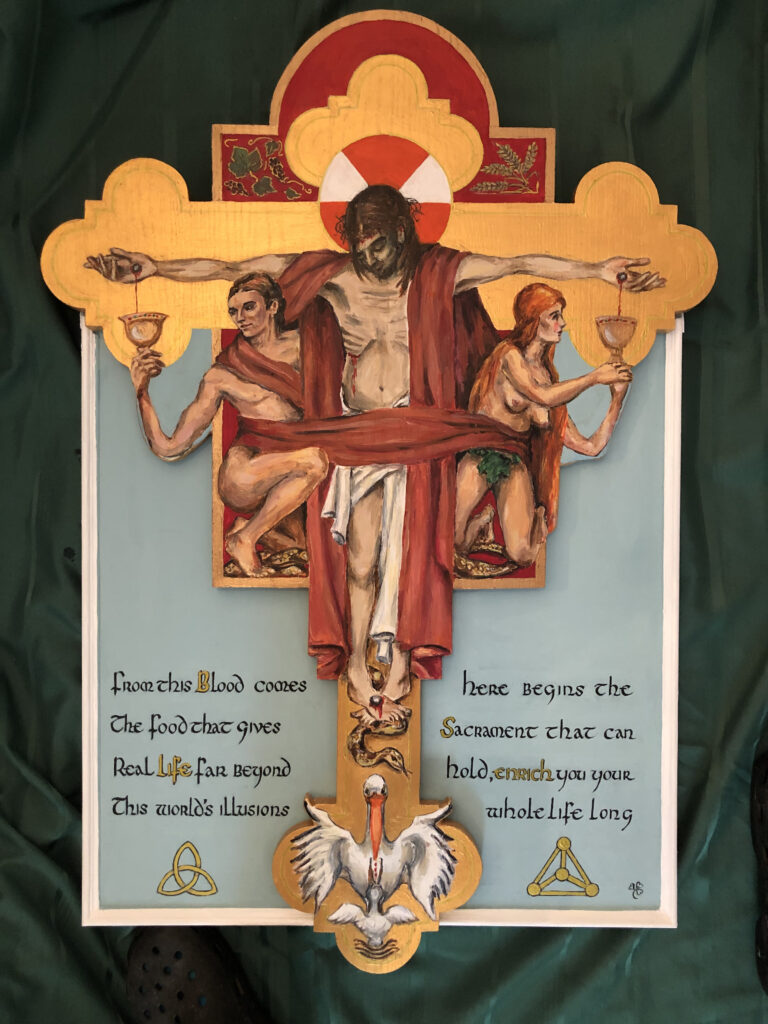

A departure from society and war work was Sargent’s mighty “The Dogma of Redemption”, a huge frieze now in Boston (US) public library, and which centres on a plaster relief of a crucifix flanked by Adam and Eve receiving the sacrament of Christ’s blood into chalices. Sargent did many studies for this, and the work was in turn much copied.

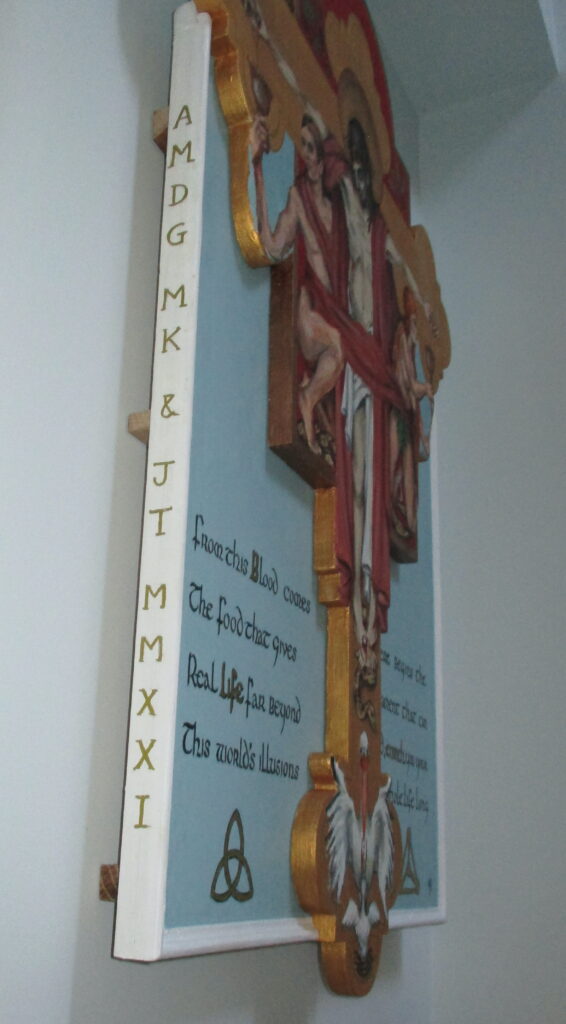

My erstwhile colleague had written a little treatise on Sargent’s Crucifixion with Adam and Eve, called “Redemption Achieved.” He then conceived the notion that he would like his own version, backed by a wood panel with text of his own choosing, to hang on his stairs. It was not an easy commission, for many reasons, partly because the angle at which I had to work gave me a stiff neck and a headache each day, and also not least because I was instructed to solve the problem of Eve’s impossible physical contortion. After some long cogitation, I turned her round in a pose resembling a page three girl. My colleague said he liked the solution, and had nothing against breasts …

The crucifix and the panel with text now hang on his stairs. They would look better on a darker wall, and – in my opinion – the whole thing would look better without the blue wood panel. But he who pays the piper calls the tune.

The parish to which I belong has a new priest. The previous incumbent departed, ending more than 350 years of association with the English Benedictine Congregation as the parish is handed over to the Diocese of East Anglia.The Waveney Valley is one of the oldest post-Reformation Catholic missions in England, as the first Benedictine priest, William Walgrave, arrived at nearby Flixton Hall in 1657. The line of service was unbroken since, with a Catholic church first being built in Bungay in 1823.

So now the monks have gone, and our new priest requested that three members of the parish pastoral council accompany him to view and record the state of the enormous Victorian presbytery, vacated only that very morning. What a powerful metaphor for the state of the Church it was: vast, with many rooms stretching out along corridors, cluttered and uncleaned, with filth and cobwebs, untouched for 150 years. Files of confidential material had been shoved into cloakrooms and left, and the heavy old cupboards and wardrobes disgorged bundles of stained bedding as their doors were opened. Maybe this Gothic horror was not only a metaphor for the Church, but particularly of the Benedictine community of Downside which served the parish for decades, and which is now tainted with the evils of child sexual abuse. I have written of the IICSA report before (see August 2018), and it was dominating my mind as we explored the dark horrors of the building.

The beauty of this September and the purity of the early mornings have tempted me twice to the coast at dawn to watch the sun rise over a tranquil sea. The dog and I walk north along the beach from Dunwich, the Southwold light ahead of us winking its warning over the mist. I throw stones into the sea and the dog plunges in to search. She is eternally puzzled by their disappearance. We turn inland over the Walberswick marshes and back along the edge of Dunwich forest. We are utterly alone in paradise.

But now as I write with the new month nearly upon us summer has left abruptly with no lingering farewell. Suddenly it is autumn, with cold nights, rain and gales. Darkness comes not long after six, and in the mornings I need my torch as we set out. “Adieu vive clarté de nos étés trop courts.” I know – I say it every year….

And to emphasise the parlous state we are in here in Britain I just heard a farmer interviewed on the BBC say that he has had to plough in five million (five million!) broccoli and cauliflower heads, for lack of both cold storage (CO2 shortage) and workers to pick them. And next year, he said, less will be grown, and again there will be empty shelves. To trash food when so many people are slipping into poverty is not just a heart-breaking waste, it is a sin; I can find no other word. Welcome to post-Brexit Britain.