But, you will say, she was going to stop; she said she had nothing more to say. She said July would be an end of Common or Garden in Suffolk. And she did mean it. However, dear reader, vanity has yielded to the flattering requests to continue, but I do so on the understanding there can be little new, and doubtless much repetition of previous years.

Cue a threnody to the departing glories of summer, to the hot days and stifling nights, to the dusty stubble fields, to a time of ease and bounty. I think that’s what you have come to expect from me at this point in the year.

Little is “normal” about this year. The word itself is in too-constant currency since we all became aware of Covid-19 and its effects on our daily lives. There is much talk of “getting back to normal,” or “the new normal,” but maybe it is a word whose use should be curtailed, for when we says things are no longer “normal,” we mean that they are not as they once were, familiar, and enshrined and defined as the status quo ante in our memory. In truth, there is no “normal” – normalcy – for life is perpetual change. It’s just that this year the change has sprung out and whacked us in the face.

Our weather has certainly not been “normal” this month, producing extremes of heat, then exceptionally dark and humid days, then storms and gales. Yet extreme is what we must become accustomed to as the warming of the planet produces our new normal. And this “normal” we have inflicted on ourselves.

As I write, in the dying days of the month, meteorological summer is thrashing its tail here in the east, doing a good imitation of autumn. So that’s a bit of “normal” – the security of the familiar, for the bank holiday here has produced weather we all recognise and are used to: lashing rain, wind, cold, and a weeping greyness that seeps into the soul. Normal August bank holiday. This, when all else is changing and passing, is how it is meant to be. We all grew up to expect it – the shivering seaside, the rain-soaked cricket pitches.

Hard then to remember the beginning of the month, when day after day – or so it seemed – we sweltered in scorching heat. Sleepless and sweating after a restless night, I went once again with the dog at sunrise to seek some breath of air at the sea. I thought that at 5.30am we should have Dunwich beach to ourselves.

Far from it: as we descended the steep shingle bank to the sea we had to dodge huddled human forms in their sleeping bags. Already families were swimming. We walked north as far as Walberswick and back, and then we both swam, the dog not leaving my side in the unusually balmy water of the North Sea.

This last idyllic taste of summer disappeared abruptly with violent storms. One night as we went out before bed we were surrounded 360° by constant flickering lightning. And after the storms came the wind, violent and destructive. Such is the exposed position of my house and garden that a gate was torn off its hinges, and yet again I lost a pane from my new greenhouse, despite its new more sheltered site. The old one was razed by storms Ciara and Dennis in February.

Heat and dust are now a memory, replaced by rain and cold, and the first log fire to cheer the chilly damp. Back to “normal.”

Harvest is finished, a poor yield this year, especially of wheat, after the water-logged fields of the winter and the extreme drought of the spring and early summer. I was going to say all is safely gathered in, but one farmer over whose land we often walk in the early morning is notoriously slow to cut. Year after year the good weather comes and goes, while his crop waits to be flattened by downpours, laid, and beginning to sprout before he stirs himself and his combine.

This year I have noted several fields of oats, which had become a rarity. They are tolerant of the damp conditions which obtained till mid-March, can be planted with more flexibility of timing, and are good as a break crop to help control the dreaded black grass. An oat field is a beautiful and a graceful thing, the grains translucent and shimmering. That they were once more common is attested by the wild oats on nearly every field margin (the top-most picture this month shows an example).

Because we walk our two hours so early in the morning to avoid heat, the young dog requires some exercise later in the day. A ball suffices for endless and insatiable amusement. To stimulate her brain and make her work we have, in previous years, done several scent work courses, during which she graduated from finding a felt mouse stuffed with catnip (easy) to detecting a hidden £5 note (quite skilled), an activity which I feel should be encouraged. When we lose a ball she is relentless in her quest to find it. In October she will be introduced to mantrailing. Perhaps she will find me a man…

After taking a visiting daughter to the station in nearby Diss (over the border in Norfolk) the dog and I once again walk part of the Boudicca Way, of which I wrote in June. We pass a lane leading to the village of Burston, and I am reminded that the first weekend of September usually sees the Burston School Strike Rally, habitually attended by the major Trades Unions, and addressed by the great and the good – and leaders – of the Labour Party. But not this year of course; this year there is no normal, and Covid has claimed another cancellation.

Many have not heard of the Burston School Strike, which lasted from 1914 to 1939, conferring an enduring fame on this tiny south Norfolk village, and making it a symbol of Socialism. I knew nothing of this before I worked on a local newspaper back in the 1980s. This is the story of the longest strike in UK history.

Tom Higdon and his wife Annie were appointed as teachers at the Burston and Shimpling Council School in 1911, but had previously worked as teachers at Wood Dalling School, also in Norfolk where – as Christian Socialists – they had objected to the poor conditions, and about the employment of children by local farmers, which interrupted their education. Many of these farmers were also school managers so the Higdons’ activities created social tensions.

Eventually, the Norfolk Education Committee gave the Higdons the option of dismissal or employment at another school. They transferred to Burston where they found conditions for many labouring families were similar to those at Wood Dalling. Tom Higdon gained election to the parish council at Burston in the hope of making improvements, while Annie repeatedly made requests for better conditions at the school.

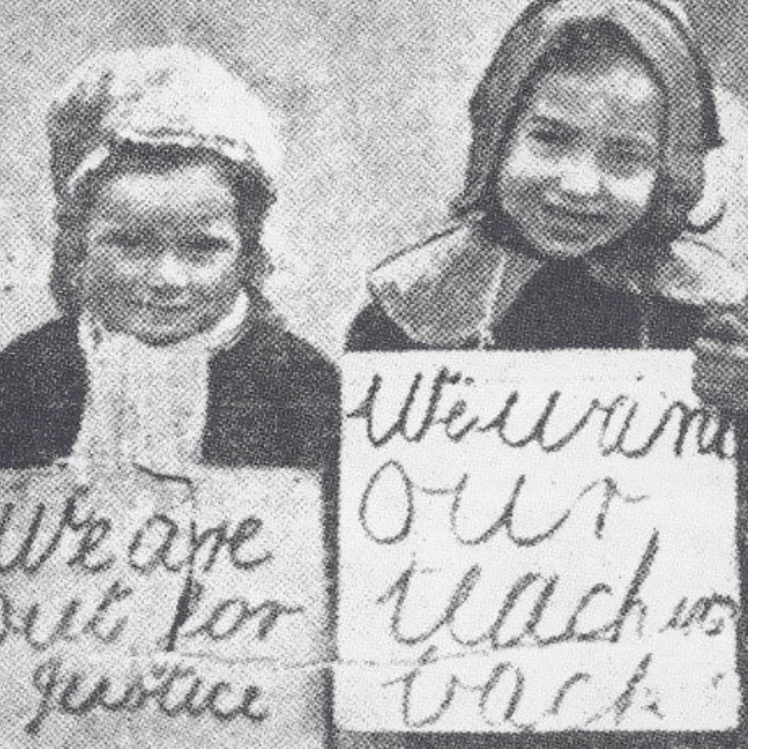

Local farmers objected, as did the Revd Charles Tucker Eland, the local rector and chairman of the school managers, a man of plentiful income and considerably less compassion. Allegations of pupil abuse were made against the Higdons in 1914 and they were subsequently dismissed. Many of the children and their parents believed the allegations to be fabricated, and on 1 April 1914 Violet Potter led her fellow pupils out on strike to show their support for the Higdons.

A separate Burston Strike School was established on the village green for those pupils and parents who refused to send them to the official council school. Many labour organisations supported the Strike School and eventually enough money was raised to build a permanent schoolhouse. It opened in 1917. The strike ended in 1939 when Tom Higdon died.

And so tomorrow autumn starts. There is much work still to be done, harvesting, picking, processing. We hear little of the Brexit talks, buried in news of a rising tide of Covid cases, of holidaymakers quarantined, of schools returning to an uncertain future. But what seems certain is that we may be in for a very rough time soon, if the talks yield no good trade deal and the end of the Transition Period coincides with a wave of Covid and winter ‘flu. Out to the garden, then; off to the hedgerows…