The dog and I are just back from our end-of-month chore of delivering village magazines to the outlying farms and houses as far as the village boundary. The dog, like a milkman’s horse, knows the round by heart, turns off the road without being told, and sits quietly while the month’s issue is deposited in the correct receptacle.

It is not really an onerous task. The walk back, having shed our burden, is a scant 2.5km, but the delivery round itself is far longer, for we are up and down paths, drives, farm tracks, and round the back of houses. The instructions are various: the magazine to be placed in the box where clothes pegs are kept, to be put on the ledge on the right-hand side inside the lobby, in a (former) litter tray inside a chest, in an old drainpipe attached to a gate with string. Don’t forget which places must have two copies… The newer houses (farm bungalows mainly, or barn conversions or extensions) of course have letterboxes, some at the base of the door requiring me to get down on all fours; some where you have to push against a draught excluder with all your might; some which want to take your hand off as they snap shut.

Most of the dwellings attest to the agricultural past – and present – of the area. We go to many farms, mostly 16th or 17th century in origin, one with a smart Georgian frontage tacked on. The smart ones have been taken over by those who have moved to the country (the obligatory 4x4s shiny in the drive), the ramshackle ones still working operations; and there are farm cottages, some thatched; farm bungalows; converted barns (holiday lets).

One particularly lovely building, grade II listed and dating from the 16th century, has stood empty now for more than three years. A mix of sadness and anger wells up as we trudge up to the door. A couple from London, she a poet and librettist, lived there. They were not married, and he died suddenly in 2019, intestate. His adult children turned her out, and the place is still not sold. But of course, we never know the full story. I saw the son once when I was delivering a couple of years back, and he told me to keep putting the magazine through the door each month. Why? For the unhappy ghosts?

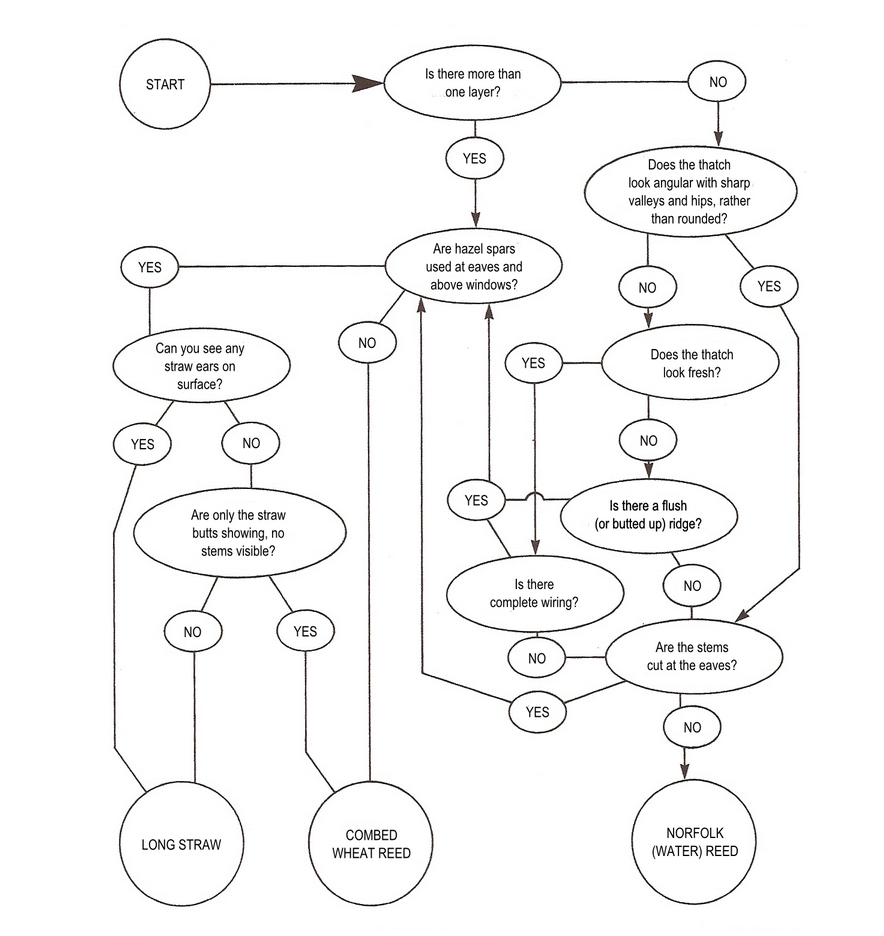

There are many thatched roofs locally, their ridges ornately patterned from the thatcher’s own portfolio with long straw, whether or not the rest of the thatch is Norfolk reed (more durable) or also in long straw. Master thatchers will often grow their own straw to ensure continuity of quality, and it is reaped and treated by hand. An expensive business! Long straw thatch in the region has the most diverse visual feature detail characteristics, which are predominately characterised by the gable ends, and I gather one would know pretty much where you were in East Anglia by the gable ends. How do you tell if a thatch is reed or long straw? See below…

On the way back we passed an orchard with daffodils in flower. They trumpeted “Spring is coming! Spring is coming!” as we walked by. There are snowdrops and aconites in gardens, and I have seen a crocus. The heart lifts a little from the mud and mire.

Yes, spring no longer seems an impossibility. The deep dark of the year is done with. At the end of January, a month which goes on for about nine weeks, there is a shift, a marked change in the quality of light. I don’t mean because the days are sensibly longer (seven hours 48 minutes of daylight on 1 January, and nine hours on the 31st), but because the landscape is now seen through the pastel screen of early spring.

There are other signs: there is a definite, if limited, chorus of birds in the early morning. The monotonous two-note song of the Great Tit has started up, and once more larks are singing high above the flat fields. The leaves of primroses are visible, and their shy pale flowers will not be long in appearing.

And good riddance to January with its lengthy gloom. The only relief (for those of us afflicted by dark and drear days) came during another week of intense cold, when once again the fields were concrete-hard, and the ice on the pools on the Common withstood my weight. Then there were magical frozen mornings when there was a hoar frost and every tree, leaf and blade of grass was coated in powdery sugar icing, the tracery of the trees producing intricate fan-vaulting against the sky. These I entirely failed to capture in photography, and have borrowed this picture by a local environmental group.

It was some compensation for the long days of rain, which has turned the Common into a water land of shining pools. Even now, though, the ponds and ditches have not filled after last year’s drought, and more is needed. Maybe February fill-dyke will oblige. I am conflicted: it is a real necessity…but those morning walks, slipping and sliding through the mud and wet and darkness.

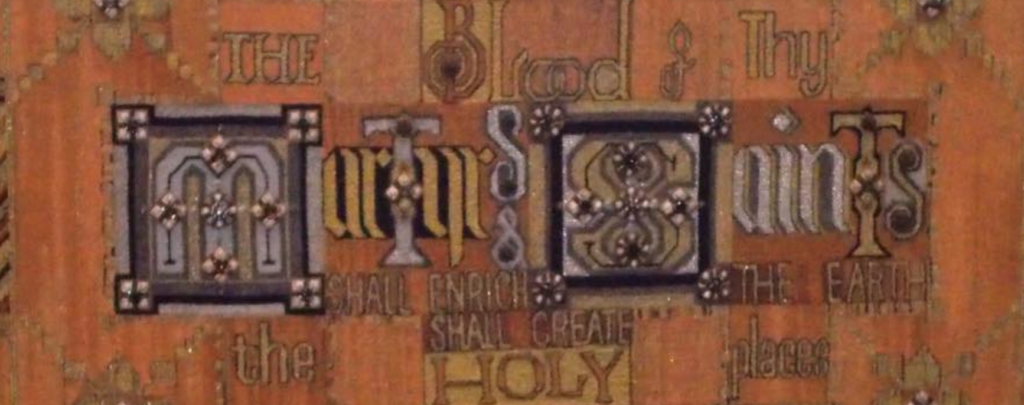

To live in the country is to be fully sensitised to the creeping change, the barely discernible shift, of the advancing year, alert to every mood of the weather. To be both a countryperson and a Catholic is to have one’s year marked out and timetabled not only by the seasons and their proper occupations, but also by the Church, its rhythm of feasts and fasts, of saints and of ‘ordinary’ time. Both these calendars ruled the lives of our ancestors, and we are losing something precious, in the perma-lit concrete of our cities, and the increasing ignorance of a world punctuated by saints and holy days. The year-round hot cross buns, the advertisements which tells us that chocolate eggs are the “true” meaning of Easter…I would hope it were possible to celebrate the growing diversity of our country without losing sight of the richness of our western European heritage, the culture of a Christian past. I was shocked recently when a friend, a life-long churchgoer from the more Protestant end of the C of E continuum, did not understand a reference to St Sebastian, full of arrows.

And here I must pay tribute to an online friend of a hagiographical bent, who has created a social media page devoted to ‘the Feast of Insignificant Saints’, which treats us daily to a (usually) obscure saint – an unpronounceable Celt, or some martyred Roman virgin. There is much to be learned. On the day I write this, for example, we commemorate Metranus, an Egyptian martyr in Alexandria, sometimes called Metras, who was killed in the year 250 during the reign of Emperor Trajanus Decius. Who knew?

I had not intended to continue this chronicle, having taken it up again, with any regularity, but it seems to have sprung unbidden this month. One note, which will demonstrate that, despite the occasional week of frost, our climate is incontrovertibly changing. On 4 January, on the Norfolk-Suffolk border, a butterfly…It ain’t right.