And suddenly – autumn: Adieu vive clarté de nos étés trop courts.

Though in truth this last summer has not been short. It has endured, nearly five months from May and on into September.

In Suffolk, that is. In Cornwall during my week’s holiday, alas, it was the week of equinoctial gales, and drenching swathes of rain. But more of Cornwall in a moment.

Some readers have complained that I have recently strayed from descriptions of my twin preoccupations: walking (the Common) and my garden. How odd and how limiting it would be if my life revolved solely around these activities. I do and I will return to them in these chronicles, but not exclusively so.

I was ready for some down time. The first two weeks of the month were spent with my nose to the grindstone, as my father would have said. Editing, sub-editing, nagging for the last bits of copy, laying out pages, tweaking, and checking checking checking – my first print journal for the Confraternity of Pilgrims to Rome. I felt I was going cross-eyed. The last time I prepared copy for publication was decades ago, not quite in the days of hot metal, but certainly before the days of digital. Maybe I have forgotten what hard work is.

I was ready for some down time. The first two weeks of the month were spent with my nose to the grindstone, as my father would have said. Editing, sub-editing, nagging for the last bits of copy, laying out pages, tweaking, and checking checking checking – my first print journal for the Confraternity of Pilgrims to Rome. I felt I was going cross-eyed. The last time I prepared copy for publication was decades ago, not quite in the days of hot metal, but certainly before the days of digital. Maybe I have forgotten what hard work is.

And so in mid-month from Britain’s most easterly county to its most westerly, for a week of holiday with the young dog. She is excellent in the car – you wouldn’t know she was there, but I am mindful of her, and my, need for exercise, and breaks from travelling, so we took the journey in two days, for the most part off motorway so there were possibilities for walks.

My years in France have caused me to forget how wearisome, crumbling and congested are the roads in this country:

The rolling English drunkard made the rolling English road.

A reeling road, a rolling road, that rambles round the shire

wrote Chesterton, but what malevolent maniac made the million Milton Keynes roundabouts?

But soon we came to the straighter roads of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, many of which are remnants of our Roman past. By chance we came across an ancient track, the Salt Way, which runs from Droitwich on its way to the coast of Hampshire. It is mentioned in a Saxon Charter, dated 969, as “Sealt Street.” Some have supposed it to have arisen from the traffic of salt from Cheshire, while others hold that the name simply implies the “Hill Way.” We stopped and walked for miles.

Thinking of how the Romans built their roads, straight as arrows cross country, always recalls my father’s passion for these tracks and paths. He possessed many books on the Romans in Britain, and when he and my mother retired it was to within a few metres of the Via Devana which slices diagonally across England from Colchester (Camulodunum) to Chester (Deva). I remember him vividly, setting off so earnestly in stout walking shoes, armed with map and compass in an old gas mask bag, to explore.

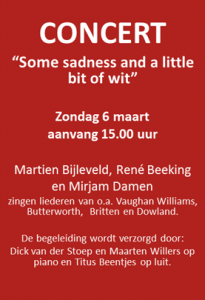

And the next day, too, this time on motorway, passing signs to Weston-super-Mare, which he insisted on pronouncing “Mar-é”, and listening to Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis, he sprang to mind. My sleepless childhood nights were disturbed by many composers, their music filling the house from my father’s two enormous stereo speakers, and a great deal of Vaughan Williams with his plangent strings. It was, I suppose, less deafening than the Wagner…

And how will our children remember us, with our own eccentricities, our own crimes against their childhood?

But to Cornwall…We stayed at Morwenstow, just west of the border with Devon, on a beautiful but murderous stretch of coast, where the cliffs are rugged and sheer.

A sailing friend wrote to me “Absolute death trap in a nor’wester and the only possible port of refuge, Padstow, even worse since it’s a bugger to get into in any sort of blow. But golly, lovely.” Indeed it was lovely when we could see through the rain.

Morwenstow seems known mainly for its strange Victorian parson, Robert Stephen Hawker. One of his main concerns became the rescue of sailors from ships wrecked on the rocks of the local coastline.  On 7 September 1842 the brig Caledonia was dashed to pieces at nearby Sharpnose Point. All but one seaman were lost but Hawker ensured the survivor was nursed back to health, while giving a Christian burial to the nine crewmen who were washed up. The Caledonia’s white pitch-pine figurehead he also retrieved, and used as the churchyard’s grave-marker for captain and crew.

On 7 September 1842 the brig Caledonia was dashed to pieces at nearby Sharpnose Point. All but one seaman were lost but Hawker ensured the survivor was nursed back to health, while giving a Christian burial to the nine crewmen who were washed up. The Caledonia’s white pitch-pine figurehead he also retrieved, and used as the churchyard’s grave-marker for captain and crew.

He built a little hut on the cliff at Morwenstow, using timbers washed up from the Caledonia and two vessels wrecked the following year, the Phoenix and the Alonzo. He’d sit on fine days smoking opium and composing his poetry, and during times of storm scour the grey waters for ships in distress. For many years he continued this gruesome duty of recovering corpses from the sea. Altogether, he rescued nearly 50 bodies. It is said he plied villagers with gin to inure them to the task of collecting washed-up body parts.

It takes a while to relax into a holiday, to realise – in the sense of making real – that I do not have to be anywhere or do anything, except keep the dog and me exercised.

To this end on the first full day, and the only completely dry one, we set off on a long trek which took us across fields, through woods, alongside streams, and to the coast at a little beach, pleasingly called Duckpool. And then back along the clifftops past the GCHQ listening station to another inlet, Stanbury Mouth, and then back inland towards “home” on country paths. Here I was genuinely scared, no exaggeration, and the thought that flashed across part of my consciousness was “Is this how it all ends?” We were crossing a big field with a large herd of grazing heifers, with a few cows and biggish calves. I think they were Devonshire Red Rubies.

There must have been 30 or 40 of them. I put the dog on the lead. As cattle will, they came towards us, and at first I thought it was just the usual curiosity, but it was soon apparent that it was aggression. Thirty or 40 large animals advancing at a trot and then a canter is truly terrifying. I followed advice and let the dog go, knowing that she could outrun them, and that she would draw them away from me. That worked at first, but then they came for me in a wide semi-circle which then drew into a three-quarters arc.

I knew instinctively that if they managed to close the circle I would be a goner, and I would be killed by trampling. It happens. I opened my jacket to look as big as possible, bellowing and waving my stick, and as the leader came at me whacked it hard on the nose. That caused it to pause, and they all stopped for a second. Then they came on again. The stile at the end of the field seemed very far off. I dared not turn my back. And so, slowly, walking backwards and praying not to stumble or trip, I managed to cross the field, bashing the nose of the nearest as they advanced, and shouting as I went. Heifers, eh…. big hormonal girls.

When we got over that stile I was shaking, and my heart racing. It’s not an experience I would wish to repeat – which is a pity as that path was our most direct to a beach. I know it is said that it is a myth that the colour red enrages bovines and that they are colour blind – but I was wearing a red jacket.

The remainder of the holiday was not without its perils, either. Storms Helene, Ali, and Bronagh battered the coast in swift succession, rendering clifftop walks unwise. One morning I had to cling to a gatepost to avoid being blown over. Inland paths, with the attendant worries about livestock, tend to peter out and the possibilities of getting lost are many. Once upon a time labourers walked to work; children went to school on foot, and these public rights of way were in constant use. Now farmers understandably do not encourage walkers, and signs disappear, and gates are padlocked, and the paths cease to exist – except on maps.

Vaughan Williams attended our return journey as well, as I listened to Radio 3’s Record Review of his “On Wenlock Edge.” My father loved what one critic unkindly called this “Cowpat Music”, the works of English pastoral composers – Vaughan Williams, Holst, Bax, Butterworth. They engender a nostalgia for a lost England, calling up a pre-War world which never was the idyll our false memory clings to.

I was reminded also of a chance and emotional encounter in France, one of those rare moments when the past bursts in unexpected on the present. Four years ago I was working in a pilgrim hostel on the Voie de Vézelay, on the way of St James in the Dordogne. Some Dutch pilgrims arrived one evening, and after supper one of them, René, got out some music and sang unaccompanied from Butterworth’s “A Shropshire Lad.” The surprise was so great, and the emotion of memory so strong, that tears came unbidden. Eighteen months later another surprise: René emailed and invited me to a concert in which he was singing at Oosterbeek.

Back to Suffolk, which had enjoyed continuing summer while we battled the wind and the rain.

And so now there is more darkness than light in the 24-hour cycle. Morning walks start later; a coat is necessary. But the legacy of this extraordinary summer lingers on in the glut of fruit. The hedgerows blaze with scarlet and vermilion hips and haws.The dog joins me in blackberrying.  Blue sloes are prolific and await the first frost for picking. Tomatoes in my garden are so numerous they fall to the ground and rot.

Blue sloes are prolific and await the first frost for picking. Tomatoes in my garden are so numerous they fall to the ground and rot.

Across the Common the horses will soon be moved to winter accommodation. August’s late foal – a surprise – has grown strong and sturdy. The ponds are dry as dust, and we wait for the winter rain.

Bientôt nous plongerons dans les froides tenèbres.