Five forty-five on a morning already hot, the hottest of the year so far. The dog and I walk south along the shore, by a gentle sea whose soothing suck and drag over shingle induces a sense of peace, and of rightness with the world. The sun, still close to the horizon, makes a silver pathway across the water.

The dog (I can no longer say “the young dog” for she is now nearer four than three) has till now never cared for water – apart from standing hock-deep in slimy and stinking ponds. It is odd, considering each of her parents is from a race of water dogs. Today, though, is different: she discovers the joy of swimming. Taken by surprise by the sudden shelving of the shore, she has no choice but to swim. She is surprised; she likes it: “Look, mummy! Look at me! I’m swimming!” And then I cannot get her out of the water – she frolics, she cavorts, she plunges, and …she swims.

We had driven towards the sunrise to Dunwich – a staccato journey, braking constantly to avoid hares zig-zagging, small rabbits playing, pigeons lumbering into flight, a muntjac, and two cock pheasants fighting, oblivious to the motorised danger. On our way back, driving with car windows down, through the shade of Dunwich Forest we hear nightingales.

Midsummer… The scents of midsummer: mown grass, honeysuckle, privet, roses, young barley on the breeze, the delicate perfume of field beans in flower. Midsummer…. The winter barley has turned and soon Suffolk will be a sea of gold. Midsummer…nights never truly dark.

Midsummer. On cue comes the St John’s Wort for the Nativity of St John the Baptist, a quarter day which signals that the year is half over. It is always a poignant moment when the solstice is past, the point of sunrise ceases its slow drift northwards, and nights begin to lengthen. More perhaps than at New Year we look both forward and back; this year more than most.

A gardener, of course, is always – Janus-like – looking forward and back, learning from the successes and failures of past sowings; looking forward to harvesting the result of hard physical toil. A gardener’s job today is always to create tomorrow out of yesterday.

Midsummer is that moment of transition, and now at this tipping point of the year I can start to eat the result of past labour – broad beans, peas, chard, courgettes, potatoes, beetroot, lettuce, onions, herbs, artichokes. The “front” garden, too, is at its best. For two or three weeks each year (as I never fail to note in this chronicle), my flower beds give a passable imitation of a real cottage garden, the abundance of flowers hiding and disguising the weeds.

At the beginning of the month, with the first tentative steps out of total lockdown, the glorious sun and warmth which had lasted all spring deserted us. New month, new weather once more. The sky became grey again and rain could be smelled on the wind before it came. It was cold as only June in England can be. A fire was lit.

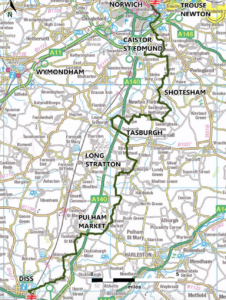

With the partial liberation we learn to place the words “socially distanced” in front of any activity involving another person or persons. On a grey windy day I met a friend for a socially-distanced walk, and we explored part of the Boudicca Way, a walking trail which links Norwich station southward to Diss, meandering – seemingly back in time to the 1950s – through the gentle South Norfolk countryside, sometimes on lanes innocent of traffic; sometimes by a river, across a ford, through pastures and meadows. We sat a while outside the tiny isolated church of St Andrew, Thelveton. No sign in the lane proclaimed its presence to passers-by; no notice told us to which saint it was dedicated. The only company was a meadow of cows and calves, guarded by a bull; the only sound was birdsong. And yet the churchyard was neatly mown, the graves tended, the headstones upright and clean.

Boudicca, or Boadicea, was of course the legendary flame-haired warrior queen of the Celtic Iceni people. Boudicca’s husband, Prasutagus, was king of the Iceni (in what is now Norfolk) as a client under Roman suzerainty. When Prasutagus died in 60 CE with no male heir, he left his private wealth to his two daughters and to the emperor Nero, trusting thereby to win imperial protection for his family. Instead, the Romans annexed his kingdom, humiliated his family, and plundered the chief tribesmen. While the provincial governor Suetonius Paulinus was absent in 60 or 61, Boudicca raised a rebellion throughout East Anglia. The insurgents burned Camulodunum (Colchester), Verulamium (St. Albans), the mart of Londinium (London), and several military posts. According to the Roman historian Tacitus, Boudicca’s rebels massacred 70,000 Romans and pro-Roman Britons, and cut to pieces the Roman Ninth Legion. Paulinus met the Britons at a point thought to be near present-day Fenny Stratford on Watling Street and regained the province in a desperate battle. Defeated, Boudicca either took poison or died of shock or illness.

Hard to think of all that slaughter as we walked the irenic green lanes.

In a few days the major part of our Covid incarceration and enforced inactivity will come to an end. Only hindsight will tell us whether we are unlocking too soon for safety, too late for the stricken economy; whether there will be spikes, second waves, more deaths, more disaster. Three months, which at the beginning might have seemed to some too long a sentence, have for me flown past. And now, reviewing, the question forces itself upon me: “What have I done with them? What have I actually achieved in this unprecedented period?”

And the best answer I can give is that of the Abbé Sieyès, priest and political theorist under the French Revolution, who – when asked what he did during the Reign of Terror – replied “J’ai vécu.” I survived. Maybe it seems obvious, looking back, that the majority of us would survive, but three months ago we looked on appalled at the Four Horsemen riding over the land. The Grim Reaper stalked us, and any careless contact, a touch, a cough could spell sickness and death. He may yet come back to get us.

What have we done with it? Have we re-evaluated? re-assessed? Have we promised that things will be different? that we shall live simply, travel less, save the planet, enjoy our loved ones, eat local produce, grow our own food, reduce stress, change our priorities? I hope so, but I am pessimistic, for I know that real behaviour change takes at least six months to become rooted in our lives.

We can now, cautiously, breathe again – for a while at least, and the existential questions recede. Time now for other worries to take over: a dear friend anxious about her octogenarian husband’s memory lapses; another who lives in a marriage of coercive control. “For better for worse…in sickness and in health.” Today we hear of a likely spike in the number of divorces after couples in three months of lockdown were forced to confront realities often evaded by long hours at work. Happy are those who can say “J’ai vécu” after years of marriage.

A friend has called these chronicles “melancholy.” Maybe that is because I am pessimistic about human nature; maybe because I am all too aware of the swift passing of the seasons, and thus that there are few remaining years for me. I don’t feel sad, only occasionally wistful for the chances missed, the graces resisted.

But hey! Who could be melancholy with the prospect of a haircut in a few days!

Lovely words again, Mary. Thank you!

What a glorious garden you have created, Mary. What a serene sense of blooming Midsummer you create here. Reflective, yes, but not melancholy. And “the dog” is swimming! All shall be well.

Lovely photographs! I came across your site while looking for information about Tongs Lane. I think we met at Christmas?

Hello Candy. I don’t think we met – though I know who you are. Thank you for your comment.