It is one of those old country saws that as the days get longer, the cold gets stronger.

I had longed for snow, real snow, not just a wet covering here today and gone tomorrow. This is a yearning for the excitement of childhood, heedless of those who cannot get to work, or whose obligations to travel are thwarted. Snow changes not just the exterior but our interior landscape as well. Rules do not apply: fires can be lit during the day, sloe gin can be drunk at coffee time; in other words – school is out.

My wish was granted, and an amber warning for the easternmost parts of Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex heralded a whole week of what felt like a holiday. A holiday from rain, from mud, and from the monotony of the quotidian. Snow came from the east, swirling, sweeping, wind howling. Thirty-six hours of it. Drifts formed immediately, closing the narrow lanes. These drifts were sculpted by the gale into fantastical shapes – castles, crenellations, cumulonimbus, battlements, billows, pillows, marshmallows, waist-deep and higher.

Round here ditches are deep, and the banks the height of a man. The first morning, when the snow is still soft and wet, the dog charges across what looks like level ground, and disappears, a good five foot down. She is lost to sight for a minute or two. I panic. Finally she scrabbles her way out. I’d have found it almost impossible to get down and rescue her, and then climb out myself. By the end of the week I too can walk across ditches on compacted snow.

The farmers come out with their JCBs to clear the lanes, and scrape the roads to a fine icy surface, impossible to walk on. They pile the snow high into walls either side, where it remains for a week or so, long after the thaw, getting grubbier by the day. The 4x4s creep cautiously along – the real farming battered 4 x 4s , not the shining four-wheeled fortresses, those must-haves of those new to country living. Towards the end of that week the wind rouses itself again to close off our roads with more drifts. A Tesco van is trapped; a John Lewis van is towed backwards to safety by a tractor. As I write, three weeks later, there is still snow in the ditches.

Walking is difficult, every step an effort with the cold gnawing at the throat and chest taking the breath away. The snow creaks under my boots. I see animal tracks – hares, rabbits, deer, and – alarmingly – all round the chicken enclosure unmistakably those of a fox.

Those of us old enough to remember will tell those who are not that of course it is nothing like the infamous winter of 1962-63, when snow started to fall on Boxing Day, and the thaw did not set in till early March. The snow banks on either side of the roads were higher than the cars, reminiscent of scenes in the Monte Carlo Rally, which held us enthralled each winter on our little television sets in the Sixties. The lake near my home froze solid, and at weekends there were crowds out skating. I was 15, nearly 16, and I remember cramming my feet into Victorian skates with their dainty buttoned boots, belonging to my grandmother.

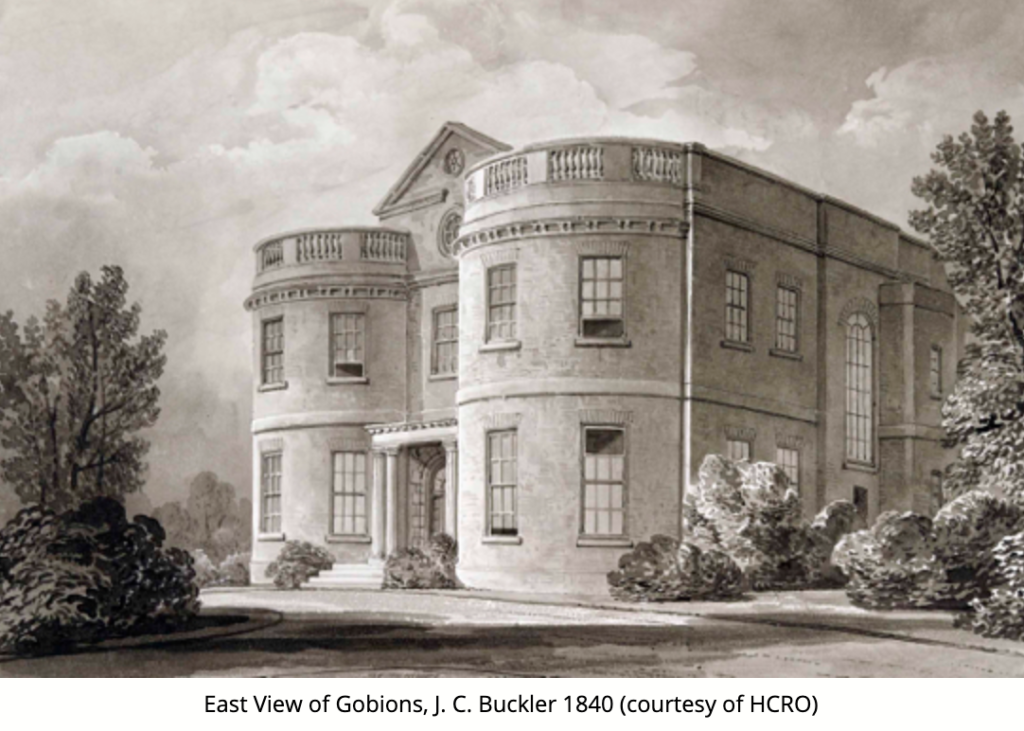

That lake had belonged to a a great house, Gobions, which had been a residence of the More family, and it is thought that Sir Thomas More, Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor, probably wrote “Utopia” there, then called More Hall (also known as “Gybynnes,” then “Gubbens”, then “Gobions”). After More’s execution in 1535 the estate reverted to the Crown, being restored to the family in 1607. Basil More sold the estate in 1693, it being purchased in 1708 by Sir Jeremy Sambrooke (d 1754), who made major improvements to the property. In 1730 Charles Bridgeman, the Royal Gardener (d 1738), was employed to make a ‘Pleasure Garden’ in Great or Gobions Wood. The wood – where I played as a child – contained various formal features, including a bowling green and canals linked by straight walks, enclosed by avenues crossing the adjacent fields and parkland. The lake on which I learned the basics of skating that winter was part of it. James Gibbs designed, c 1740, a temple facade to terminate the largest canal, together with the large Folly Arch, a three-storey gothic gateway, to terminate one of the main avenues at the southern boundary of the estate. Daniel Defoe, ten years later, called the place “one of the most remarkable Curiosities in England.” I well remember Folly Arch, which I cycled past on the way to buy bread in nearby Potters Bar. In my childhood what is now suburbia was rural.

If you are still reading, here comes one of those amazing six-stages-of-connection coincidences.

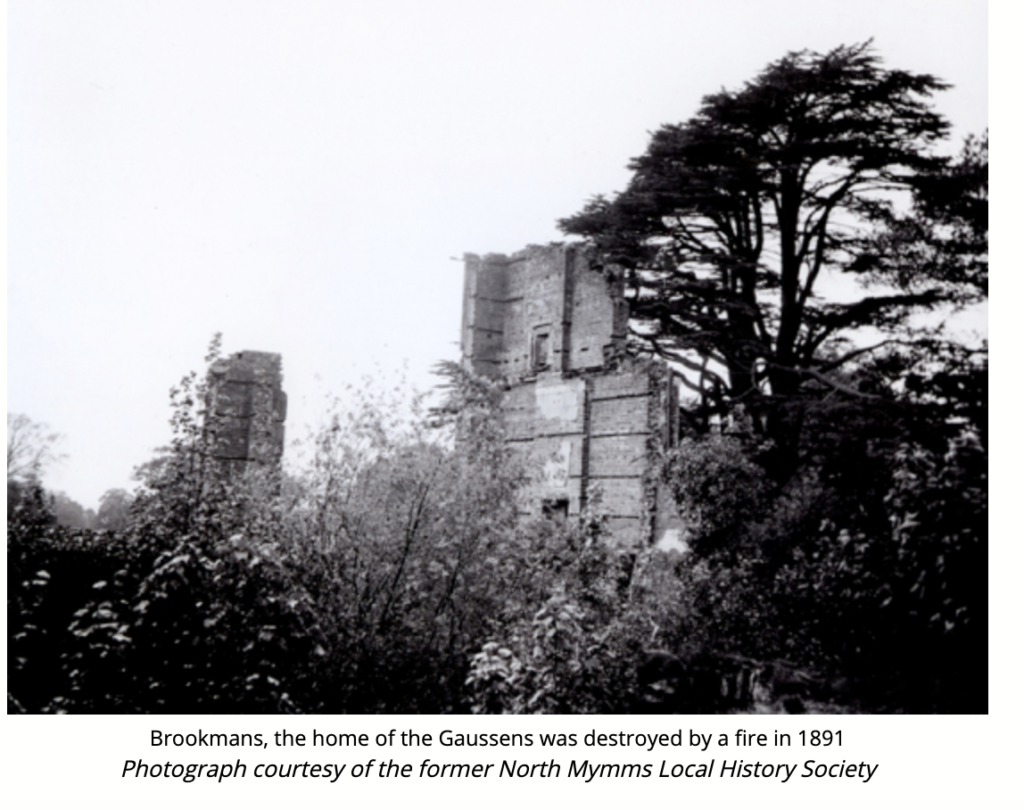

In the summer of 1968 a friend and I, having just graduated, were hitch-hiking round France. In Provence, in the Var département, we had had a lift with an elderly gentleman, who invited us to his beach-side house in Six-Fours-les-Plages for a meal with his wife. These things happened back then, and innocently. During the meal they of course asked where we came from, and I mentioned Brookmans Park, assuming they would have no clue other than my saying it was north of London. “Ah! come with me,” said the gentleman, and he led me into a dark backroom where an ancient lady sat in a chair: his mother, whose age he said was 100. As a girl this woman had been in service in the great house in the Gobions and Brookmans estate, belonging then to the Gaussens family, which had burned down in 1891. She named the landmarks for me, and remembered that lake where I had skated during the long cold winter of 1963. I remember nothing more of her story, save for this coincidence. Being so young myself I didn’t think to ask how a teenager from the Var had come to work in a grand house in Hertfordshire.

And now, suddenly, it is spring. After the snow the temperatures soared. The snowdrops are nearly finished; banks and ditches are star-spangled with primroses; daffodil trumpets proclaim the change of season, and daily the morning orchestra of birds swells and grows. The sun appeared after what seemed like months, and remained in a radiant blue sky for some days waking the energy in the earth – and in me. A spark of hope was lit, and flickers. There’s a long way to go yet.

I leave you with a stone found on one of our walks under a bench in the churchyard at Wingfield (see September 2019). I note the message.