A note to the new reader: to understand where I am coming from, in both senses, first read the static information pages in the sidebar to the left: Introduction – The Common – The Garden.

____________________________________________

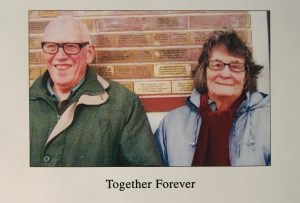

She lived just nine months longer than her husband, in what she saw as exile from the cottage which had been their home for more than half a century. This same cottage, a couple of hundred meters away from mine, is now abandoned, eventually to be knocked down by its new owner, if it doesn’t fall down first.

She lived just nine months longer than her husband, in what she saw as exile from the cottage which had been their home for more than half a century. This same cottage, a couple of hundred meters away from mine, is now abandoned, eventually to be knocked down by its new owner, if it doesn’t fall down first.

He had been ill for three years or so, long since unable to do their twice-daily regular-as-clockwork walk round the Common. The muscle-wasting and the breathlessness became so bad they decided rather abruptly to sell and move to a bungalow in a nearby market town, where there were the advantages of no stairs, and a wet room where he could shower seated. A month after they moved, he died, leaving Margaret coping not only with his loss, but with that of all that had been familiar for 55 years, symbolised for her by the fine open view of their field and trees. All she could see now was a fence, a wall, and other houses.

She didn’t die of a broken heart, they said, but of an infection following an exploratory gall bladder operation. But I think the heart had its part to play.

Poignantly, the family mourners gathered at their now-deserted cottage, and the hearse drove round the Common, retracing the familiar footsteps of the couple’s quotidian constitutional. The village church was full, and you could see that most people were of an age when every funeral must recall many previous, and is a reminder that one’s own cannot be far in the future.

The women seemed not to notice the fact that, although the previous day had been oppressively humid and hot, the weather was now more like November than July – cold, blustery, wet. Bare, fleshy arms were on show in Sunday best. The men wore their funeral suits, waistbands and waistcoats ever tighter. The many grandchildren are now young adults – thin boys and girls with dark circles under their eyes, in unaccustomed black.

I hope the family were happy with the funeral (pronounced “fooneral” in Suffolk), but it seemed too quickly dispatched, brief almost to the point of disrespect, the portly vicar being known for his economy of effort. All that kept its being over in less than 20 minutes was a lengthy eulogy by one daughter, a fine comedic performance instructing the assembled company in the social mores of matrimony and housekeeping in the mid 20th century. Most of the congregation would have needed no reminding.  Some perfunctory prayers and it was over.

Some perfunctory prayers and it was over.

Last summer, the morning after the referendum in which the UK voted narrowly to leave the European Union, I went next door to have a chat with John and Margaret. The conversation went like this:

Me: Are you happy with the result?

Margaret (emphatically): Oh yes, I voted “leave.”

Me: Why?

Margaret: Because we had to pay money for the family of that man with a hook in his arm.

A moment’s puzzlement: was she talking of pantomime – Peter Pan and Captain Hook? Enlightenment – she meant the payment of benefits to the daughter-in-law of Abu Hamza, the Egyptian imam deported to the USA on terrorism charges. And for reasoning such as this, dear reader, the UK is now committing economic, political, social and moral suicide.

But all this was forgotten in the farewell after the funeral. After the committal in the chilly churchyard we left, each pondering his or her own memories, or the intimations of mortality, with “Abide with me” ringing in our ears:

Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day;

Earth’s joys grow dim, its glories pass away;

Change and decay in all around I see:

O thou who changest not, abide with me.