I am British; I obsess about the weather. The reader over these past 11 posts will have noticed.

It is almost impossible to believe that two months ago my front garden was under water, as was my drive. But since the beginning of May scarcely a drop of rain has fallen. It is not just here in East Anglia, traditionally the driest corner of the UK, but country-wide. Rainy Northern Ireland has a hose-pipe ban. There are wild fires near Manchester, one of the wettest parts of this island.

It is not just the drought, with cracked earth and shrivelling crops, but the sun – now at its zenith – blazes down from a deep blue sky with Mediterranean intensity. The dog and I walk in the misty cool of the very early morning, and now she lies panting in the shade.

I am a gardener, and so the concern with rainfall, or lack of it, and sun is of importance. For a few weeks in early summer my garden gives a tolerable impression of an English cottage garden,

but now it is tired, dusty, thirsty. The vegetable plots at the rear of the house are also thirsty, but they are at least yielding their first fruits, and few actions give me greater pleasure than picking my supper; so far broad beans, French beans, courgettes, chard, onions and potatoes.

The watering is constant and time-consuming. My five water butts are long since empty. I remember when I bought the first water butt. I went to a builders’ yard to buy some breeze blocks to stand it on:

Employee in yard: what do you want?

Me: some blocks to stand a water butt on.

Employee: do you have a big butt?

…Collapses in giggles.

This hot, dry, burning weather has accelerated the passing of the seasons. At the beginning of June we were scarce into early summer, but midsummer with its flowers has raced past, and now high summer is here. The barley is ripe for the harvest. All in the space of a month. Gone are the cascades of dog roses in the  hedgerows, the early summer meadow flowers; gone too is the full-throated dawn chorus, replaced by the incessant and insistent cheep cheep cheep of baby birds, beaks constantly open to be fed by exhausted parents. Soon they will all be fledged and gone.

hedgerows, the early summer meadow flowers; gone too is the full-throated dawn chorus, replaced by the incessant and insistent cheep cheep cheep of baby birds, beaks constantly open to be fed by exhausted parents. Soon they will all be fledged and gone.

When spring burst upon us at the beginning of May after months of cold and wet nature’s overdrive ensured that what is usually spread over many weeks happened in a rush. And so the grass seeded all at once, making for one of the worst hay fever seasons I can remember. When I was a teenager taking exams (which in those days happened towards the end of June) that was when hay fever was at its height. Rain was fervently prayed for to damp down the pollen, and when this didn’t happen I sat exams doped and foggy with primitive antihistamines. This year hay fever attacked from mid-May onwards. I walk, dosed with eye drops, nasal spray, Vaseline smeared round the eyes, and dark glasses on. A friend, whose cognitive faculties waver occasionally, suggested I go out in an eye mask…

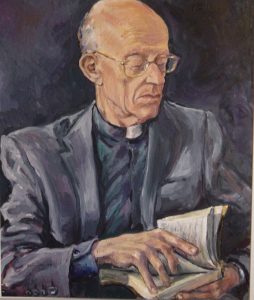

There have been few excitements this month. Generally I prefer it that way. One of them has been a portrait commission from someone I have never met (but of whom I had heard, for he is famous in some circles) who chanced to see some of my work on Facebook. This is so boosting for an ego which inflates and deflates with every puff of wind. I do not generally work from photographs, for how can you convey the reality of a person without his presence? Flattered, I agreed. It has – I think – gone well; the commissioner was happy (good, since he had paid up front). Because the recipient, its subject, is as yet ignorant of its existence I can give no further details, but will include photos next month. And the reaction of the recipient.

The other major event for me this month was attending the massive march in London on 23 June (the second anniversary of the disastrous, ill-thought-out referendum) to demand a people’s vote on the final Brexit deal. I still cherish a very faint hope that the lunacy can be stopped. It was a wonderful event, with more than 100,000 participants from all over the UK, and a particularly large Irish contingent – unsurprising when one thinks of the effects of our leaving on the Republic of Ireland, and on the North, where I have family interest, and fear a kicking-off of the simmering resentments there if the deal does not satisfy both sides of the border. There were people too from all over Europe.

Two days before the referendum of 2016 I was sitting on a train in Italy, chatting in a mixture of stumbling Italian, English and French to an Italian woman who said “Please, no Brexit. Please. We need you. All of us need each other.”

I believed then, as I do now, that the days of the sovereign nation state are long gone; we cannot recapture them, if that is what is meant by “getting our country back”. It is incomprehensible to me that people cannot understand that unity – community – is better, more productive, safer than standing alone, grasping for illusory better deals, trying to shut our doors against all comers.

I believed then, as I do now, that the days of the sovereign nation state are long gone; we cannot recapture them, if that is what is meant by “getting our country back”. It is incomprehensible to me that people cannot understand that unity – community – is better, more productive, safer than standing alone, grasping for illusory better deals, trying to shut our doors against all comers.

There is one way in which I hope we can regain something of a lost Britain: we were once welcoming to the stranger, the exile, the dispossessed. We took in those who needed to come to our country, and they became part of who we are now. This is our richness as a country – not this “little England” pull-up-the-drawbridge pettiness of spirit. We are historically a bastard race, we have a bastard language. That is part of our strength – absorbing what the newcomers have to offer, and in turn embracing them. I do believe we shall be the poorer when we leave the EU. Poorer economically, politically, culturally, morally and spiritually.

But in the past week or so fortress Europe has fortified itself further. Populist governments are taking sterner measures to keep out the dispossessed seeking a better, safer, life. Italy turns away ships; more migrants drown; Macron continues to turn a blind eye to the gross abuses of human rights in northern France; Hungary is intransigent; Merkel’s position is threatened by right-wing politicians; asylum seekers kill themselves in despair in our own detention centres.

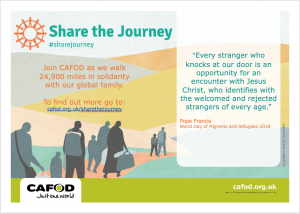

To protest at our policies, and to stand in solidarity with refugees and exiled people two friends and I organized a “Share the Journey” walk for our parish, and filled in cards to be sent to the Prime Minister, asking her to work with world leaders to ensure respect for the human rights and dignity of exiled peoples. Not many came.

To protest at our policies, and to stand in solidarity with refugees and exiled people two friends and I organized a “Share the Journey” walk for our parish, and filled in cards to be sent to the Prime Minister, asking her to work with world leaders to ensure respect for the human rights and dignity of exiled peoples. Not many came.

And here ends the lesson for this month.

The year has turned, the solstice has come and gone, and the sun has started its slow decline. But for the moment it shines bright from a radiant sky. It is summer, and the living is easy.