I am finding it difficult this month to start with what may be the expected paeon of praise to spring, to the advancing greenery, to the hope of summer.

It is nearly two years since I started these chronicles, and if they serve no other purpose they are at least a record of the weather in this part of East Anglia. We are unlikely here on England’s eastern shore to suffer the worst of Atlantic weather – the floods or storm-force winds, but trends are visible. I am not going to make the mistake of confusing weather with climate, nor am I among the ignorant who say on a warm sunny day “Oh, if this is global warming I’m all for it.”

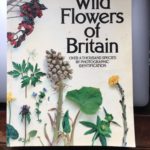

Trends are indeed visible, and they do witness to changes, differences which affect – albeit subtly – the environment in which we live, more obvious probably to those of us who live away from cities. I own a book “Wild Flowers of Britain”, published in 1977, which in the section “How to use this book” tells the reader “The flowers are arranged in calendar order.” It gives approximate dates, allowing for geography. Now more than 40 years on it is obvious that the signs of spring and summer are arriving far earlier than they were when my children were little. Of course, there are exceptions. For instance, the orchids on the Common this year appeared later than last year – odd when you consider last year late winter brought the notorious Beast from the East, and yet February this year had us sunbathing.

Trends are indeed visible, and they do witness to changes, differences which affect – albeit subtly – the environment in which we live, more obvious probably to those of us who live away from cities. I own a book “Wild Flowers of Britain”, published in 1977, which in the section “How to use this book” tells the reader “The flowers are arranged in calendar order.” It gives approximate dates, allowing for geography. Now more than 40 years on it is obvious that the signs of spring and summer are arriving far earlier than they were when my children were little. Of course, there are exceptions. For instance, the orchids on the Common this year appeared later than last year – odd when you consider last year late winter brought the notorious Beast from the East, and yet February this year had us sunbathing.

This year April has been true to form, throwing all the seasons at us. A damp and grey start, and then a sharp blackthorn winter. For those who do not know, the blackthorn winter, in rural England, is a spell of cold weather, usually in early April which often coincides with the blossoming of the blackthorn in hedgerows. The pure bridal white of the blackthorn blossom, which appears before the leaves, matches the snow or frost covering the fields nearby. And we did indeed see flakes of snow fluttering on the icy wind – when we were not being battered by sudden hailstorms.

This was rapidly followed by a glimpse of summer. The late Easter festival saw record temperatures in all four countries of the United Kingdom when we all know that it is enshrined in law that public holidays must be cold, wet and miserable. The warmth is like a loving embrace – all the tensions and contractions of the muscles which come from the cold and bitter east wind disappear. And then, so we should not get too used to this, came Storm Hannah, bashing down my flowers and broad bean plants as she blew. More panes out of the greenhouse. Gardeners know they can never win.

But the one dominant feature of our weather here has been exceptional dryness, and this is a worrying trend. Last year’s beautiful summer brought virtually no rain; the autumn was dry; and winter when rivers and ponds should fill saw significantly less precipitation than usual – with a spell of high temperatures in February.

My drive will usually flood several times each winter, and often in summer, so much so that it has to be pumped out before the postman can venture up. This winter…one puddle, which quickly drained away as the water table is so low. The ground is cracked and concrete-hard; stream beds and ditches are dry. My vegetable garden has already taken the contents of four water butts.

Of course there are always variations in weather, and we used to say that Nature will always make up for these. But now…?

I do not need here to rehearse the causes of the man-made catastrophe facing our planet that is climate change: it would not persuade those who remain unconvinced or who do not care, and those who do care do not need telling. It is very much in the public eye at present thanks to the efforts of Extinction Rebellion, School Strike for Climate, and David Attenborough and other environmentalists. Odd that it should take the urgent voices of a nonagenarian and a teenager to catch the public ear.

But have they? If I stopped ten people in the street and asked “Who is Greta Thunberg?”  how many would know who this surprising 16-year-old prophetic voice from Sweden is and what is her message? Even if they knew who she was, and that she was begging the governments of the world to declare a climate emergency and act on it, and increase targets for reduction of emissions and the deadline for these, would they – and we – be prepared to make the life changes necessary to save our world? Am I?

how many would know who this surprising 16-year-old prophetic voice from Sweden is and what is her message? Even if they knew who she was, and that she was begging the governments of the world to declare a climate emergency and act on it, and increase targets for reduction of emissions and the deadline for these, would they – and we – be prepared to make the life changes necessary to save our world? Am I?

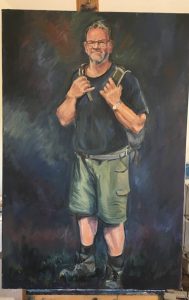

I know from a decade spent as a fitness instructor qualified to take referrals from the NHS for various medical conditions (mainly, I have to say, obesity and its co-morbidities), and from my own life, that long-term behaviour change is neither easy nor simple. Am I prepared to give up driving? I live in an isolated rural spot with no public transport. Am I prepared never to fly? How then would I be able to see my grandchildren and daughter across the Irish Sea? Six weeks of Lent (virtually) without meat were not difficult, but would I do this permanently? The arguments rage within my head, and my heart.

Just because a task is enormous and seems impossible does not mean it should not be tackled:

And I think it’s not sufficient to say to ourselves “Well, I can start in small ways. I can recycle more; maybe turn down the thermostat a bit.” It’s really not enough. Listen to Greta Thunberg: “I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. And then I want you to act.”

I will, in company with many others, and particularly as a CAFOD supporter, be going to Westminster on 26 June to lobby my MP. Ah, my MP…a junior Environment Minister. A Catholic. But also a party loyalist who – despite voting Remain – wishes to deliver a Brexit which will see us no longer bound by Europe’s strict environmental laws.

Greta Thunberg makes no secret of the fact that her clear-eyed, single-minded mission to save the planet is made possible by the “gift” which is her Asperger’s, which drives her: “I overthink. Some people can just let things go, but I can’t, especially if there’s something that worries me or makes me sad…. It’s nothing that I want to change about me, it’s just who I am. If I had been just like everyone else and been social, then I would have just tried to start an organisation. But I couldn’t do that. I’m not very good with people, so I did something myself instead.”

In the same week I heard Greta say this, I heard environmentalist Chris Packham  who also has Asperger’s Syndrome, say much the same. It means he struggles in social situations, has difficulty with human relationships (preferring dogs to people), and is, by his own admission, “a little bit weird”. He, too, knows this makes him the person he is today, and enables him to campaign, some would say obsessively.

who also has Asperger’s Syndrome, say much the same. It means he struggles in social situations, has difficulty with human relationships (preferring dogs to people), and is, by his own admission, “a little bit weird”. He, too, knows this makes him the person he is today, and enables him to campaign, some would say obsessively.

And now a personal bit. I also struggle. I know that my obsessive thinking helps me to drive things through, get things done, campaign (in a very minor way) about issues of social justice, refugees, an end to world poverty, and gives me the grit to push through my own physical challenges, and achieve ( a favourite word of my father’s). But the downside of the condition is (among other things) intolerance, incomprehension, pedantry and an over-literalness – an incomprehension that people do not actually mean what they say or write (it took me years to understand that when people say “See you later” instead of “Goodbye” it doesn’t mean they intend in fact to see me later). Add to that the miseries of misophonia and misokinesia which mean I impose physical isolation on myself and if possible shun group situations, and I would say it is a condition that does not win friends. But hey – I can remember telephone numbers and dates, so not all bad then (that’s a joke. But I often don’t get jokes). Do I want to be me? Not really. It’s uncomfortable.

So from April to Asperger’s via climate change. Maybe May will bring more cheerful news.